The World Lighthouse Hub

A13: The Phoenicians

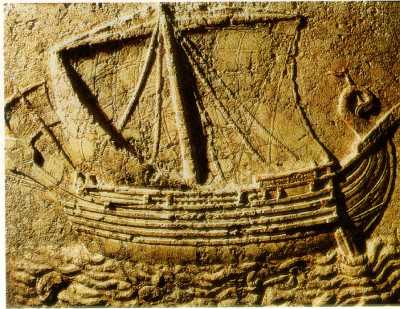

Fig. A13.1: A Phoenician Ship

Diadorus (V, 38, 3) wrote, "The Phoenicians... from ancient times were skilled in making discoveries for their own profit." Masters of the sea, they found new sources of wealth and skilfully liased between otherwise non-communicating peoples in the capacities of 'honest brokers' so as to make a profit on business transactions. They were not intrinsically a warlike people, although they were occasionally forced to defend their interests, particularly so as Roman aspirations increased. They created an extensive network of settlements and had armed forces both on land and at sea, their most famous general being Hannibal who used elephants to reinforce his army and embarked on an epic journey across the Alps to attack the Romans.

The Phoenicians were able to travel by sea across the length and breadth of the Mediterranean, and far beyond, befriending those who lived around its shores and indulging in trade to mutual advantage. In so doing, they absorbed all the best ideas of the cultures with which they came into contact, extending the bounds of their own culture, and becoming highly skilled in arts and technology [16]. Others envied their wealth, power and influence, so they made enemies as well as great financial profits. The Greeks were fearsome rivals and by the 5th and 4th centuries BC, they despised the Phoenicians, branding them as pirates who had introduced the despicable sins of greed and luxury into Greek culture. Since many of the documentary records emanate from Greek writers, the Phoenicians are often described in disparaging terms and made out to be violent, unruly and immoral people, possibly out of jealousy for what they had achieved. However, we know that the Greeks considered trading to be a lowly profession, incompatible with the aristocratic aspirations and ethics of the Greek culture. Only rarely was admiration expressed. The Roman scholar Pomponius Mela (I, 12) wrote, "The Phoenicians were an intelligent people who prospered both in peace and in war. They were outstanding in literature and other arts, in mercantile and military navigation, and in the government of an empire." It is sobering to imagine how much more we would have known about them had not Carthage been almost completely destroyed by Roman anger.

Fig. A13.2: A Phoenician ship depicted on a coin.

The Origins of the Phoenicians

One interpretation of the origins of the word Phoenician is that it derives from the Greek p(h)oinix (singular) or poiniki (plural) used to describe people who lived in Canaan. Another is that it originates from a word for the colour purple or purple-red (Greek, phoinos) and consensus is that it was applied to a people who traditionally dyed their textiles in that colour [6]. The land in which they lived was Canaan, although this name really describes the whole of the Syro-Palestinian area - a larger area than the Phoenicians occupied. Nevertheless, the term Canaanites is generally applied to them, but could include non-Phoenicians. On the other hand, the second common description of them as Sidonians is too narrow for they inhabited a region larger than the city of Sidon in present-day Lebanon.

It is only from around 1,200 BC that we can truly speak of a people called Phoenician living in the coastal area of the eastern Mediterranean, which today is part of Lebanon, Syria, northern Israel and as far south as Gaza. Before that, ancient relations between the people of Egypt and those of the near East had existed for centuries. There were undoubtedly settlements of enterprising peoples in the coastal strip regions, but they were not large enough, nor was their level of civilisation sufficiently well developed, for them to be seen as living in identifiable cities or to have a significant group identity or culture. There is a reported ‘dark age’ for the eastern Mediterranean between 1,200 and 1,000 BC when, following the end of the Trojan Wars, there was a big redistribution of peoples around the region that resulted in much unrest and instability. An interesting event of this time is the reported ‘Invasions of the Sea Peoples’ about which uncertainty remains. These invaders emerged from the Aegean along southern Asia Minor by land and sea, to the coasts of Syria and Palestine. Cyprus did not escape the troubles. The Sea Peoples were eventually defeated in Egypt in 1,180 BC by Rameses III, as a result of which many of them turned back and settled in Palestine [7]. All of these disturbances put a brake on the development of the Phoenicians and others, but from 1,000 BC stability returned and the Phoenicians continued to expand their cities and their colonies.

The region that came to be called Phoenicia extended from Ugarit in the north to Gaza in the south, and was focused on the major centres of population called Byblos, Sidon and later Tyre. It was from 1,200 BC that Phoenician cities emerged as independent entities with a clear identity. These cities, Aradus, Byblos, Berytus, Sidon, Sarepta and Tyre, were situated along the coastal strip between the sea and the mountains of Lebanon. Since these mountains frequently reached the coast, the cities tended to be somewhat isolated and existed politically as a number of city-states, rather than as a single unified nation. The cities were founded on rocky promontories that could have both a north and a south port for use depending on the weather. Alternatively, the Phoenicians liked to settle on islands that could be easily defended. Thus, when Alexander the Great decided to conquer Tyre, he had to build a causeway to reach the island [8].

Fig. A13.3: An image of the 19th century lighthouse at Cadiz

From 1,200 BC, the Phoenicians entered a new phase of colonisation, spreading their presence across a far greater area than they had until then. The cities they created had the same characteristics as in the east: Carthage and Nora were founded on promontories, whilst Motya, Sulsic, Cadiz and Mogador were founded on islands. The founding of Lixus in Mauretania and Cadiz (known as Gadir) in southwestern Spain took place about 1,110 BC according to information in several ancient textual references, with Lixus preceding Cadiz by 'a few years'. However, no archaeological evidence has yet been found to date the presence of the Phoenicians in these areas before 800 BC. One scholar does argue that a bronze figure found in Spain proves the Phoenician presence in the Straits of Gibraltar region from the middle of the second millennium BC [14]. On the other hand, Aubet [9] argues vigorously that the lack of archaeological finds in Cadiz before 800 BC fixes the date of the founding of Gadir no earlier than this. The reported date of 1,110 BC, she argues, is in error because of a confusion of history and mythology surrounding Heracles in classical Greek texts.

The Phoenicians were pre-eminent in the spread of technology around the Mediterranean. The initial driving force for the establishment of the settlement at Gadir – in the Atlantic Ocean and outside the comparative safety of the Mediterranean – was to gain access to the rich deposits of silver in southwestern Spain around Tartessos. Gadir was founded on three islands that the Phoenicians called ‘gdr’. The Greeks and Romans developed this into Gades, a plural word that reflected the fact that three islands were involved. Whether from 1,100 BC or 800 BC onwards, this proved to be the greatest entrepreneurial step the Phoenicians ever made, for the huge amounts of silver, gold and tin shipped from Gadir was the source of great wealth and the envy of many would-be competitors.

Although it is thought that the smelting of iron was invented in eastern Anatolia around 1500 BC, it was the Phoenicians who, by virtue of their ability to travel, learned that skill and then exported it to other places. This gave rise to an entire period of human cultural evolution known as the Iron Age (1,200 BC – 555 BC). As great seafarers, the ability to use first bronze and later iron resulted in superior ships, better able to travel the great distances that were becoming the norm. The use of iron nails, for example, allowed big improvements to ship design. Pieces were joined more effectively and the flat hull of older vessels was replaced by proper keels that acted as the backbone of the ship onto which the skeleton was fixed.

The main objective in the great voyages made by the Phoenicians was in the trading of metals - gold silver copper, lead and tin. The use of metals was the key to advances in civilisation. Precious metals represented wealth and were symbols of the success and development of a culture. More importantly, copper, tin and lead were for making the alloys needed for the tools and weapons with which strong civilisations exercised their power over weaker ones. The Phoenicians had other objectives too, not least of which was the desire to interact with other civilisations and to expand their sphere of influence amongst them. The zenith of this objective was achieved in the foundation of Carthage.