The World Lighthouse Hub

H14. Coal

Q: How was coal used for aids to navigation?

The choice of fuel for use in a light source was generally determined by its availability. For centuries, coal has been used as a fuel for lighthouses, in those locations that could be most easily supplied. One of the earliest lighthouses that used coal was at Newcastle-upon-Tyne which was located close to a coalfield. The physical effort involved in shipping the coal to the lighthouse site, together with the effort expended in getting it to the top of a tower, if there was one, can not be overstated.

Coal was often contained in a metal holder called a brazier of chauffer and raised to a given height above the surrounding area to give it increased visibility over the sea. An original example of a coal chauffer can still be found in the botanical gardens on the island of Tresco in the Isles of Scilly, England. This chauffer was used from 1680 onwards in the old lighthouse known as Scilly, which is today a private house on the island of St. Agnes.

Coal fires were originally used on headlands and, over the years, would have been refined by the use of improved containers to allow the coal to burn more efficiently, i.e. with more light emitted per given quantity of fuel and with less smoke. This latter is always a problem because it obscures the light and creates soot which causes other disruption. Later, fires were enclosed inside structures made of arrays of panes of glass, called lanterns. Unfortunately, unless great efforts were made to control the smoke, the glass was frequently coated in soot which reduced the visibility of the fires.

There are many examples of lighthouse towers standing today which were used for coal fires in earlier times. The old tower at Skagen is a beautifully preserved example, as also is the lighthouse at Falsterbo in Sweden and the towers at North Foreland and Lizard Point in England.

Wooden lever-arm arrangements were constructed to elevate coal braziers. These were called swape lights or vippefyr, and such a device was used at Spurn Point. Because of their nature, there are no known examples of these old lights in existence today, but replicas of vippefyr can be found in Denmark and Sweden.

The following additional information is provided with the help of sources quoted.

Gas works were common at one time, especially in Ireland where John R. Wigham, the great advocate of gas, had met with some success. At Baily and Wicklow Head many of the associated buildings and yards remain, but none is in use and no apparatus survives. A great deal of coal was needed for the preparation of gas and this entailed the making of good roads which were costly to build and maintain. [Hague, 1974, p111]

Funnels were used to great advantage in coal fires where a draught to a grate could increase the light efficiency. The fire burned hotter, brighter and with less smoke.

The vippefyr at Skagen, Denmark

Pederson Groves in Denmark invented the lever light, also known as a swape light or vippefyr in 1625. A basket containing burning coals is raised to a height of 4 to 10 m above the ground or on top of a tower.

The consumption of coal varied depending upon whether the fire was enclosed or not, upon the weather, and upon the number of hours of darkness that the fire was lit. Additionally, it depended upon the skill of the keeper in maintaining his fire. Amounts used (tons per annum) were as follows: Isle of May (1799) 350-400; Isle of May (1786) 200; Cumbrae (after 1761) 180; Cumbrae (before 1761) 160; Kullen (1791) 112; Scilly 107; North and South Forelands (1698) 100 each; Kullen (1793) 61; Lowestoft 40; Frehel 31. These amounts include coal used by the keepers for their own cooking and heating, which might be 10 tons per annum.

At Cumbrae, the light was 404 feet (130 m) above sea level and all coal was shipped to the island in the Firth of Clyde and raised through that height to create the light. Deliveries were by cart, each carrying about 9 cwt. From 1757, an average of 310 cart loads were required per annum, equivalent to about 160 tons. This rose to an average of 400 cart loads per annum in 1793, equivalent to 180 tons.

When Robert Stevenson visited St. Bees and Skerries in 1801, the keepers informed him that they used 130 and 150 tons per annum respectively. The open grate supplied for the Isle of May after 1786 burned up to 400 tons per annum, which seems to have been a maximum; 366 tons were brought to the island in 1799. During one particular stormy night, three tons were burnt requiring the unceasing attention of all three keepers.

Bellows were used with great effect to provide a focused draught of air used to improve the combustion of a coal or wood fire.

Coal fires were sometimes enclosed in glazing and gave a smaller but steadier glow. They consumed less coal and were altogether easier for the keepers to maintain. Of the 21 coal fires in Britain in 1760, nine were enclosed. Enclosing coal fires did not always provide a satisfactory result for all. Fires at the North and South Forelands were enclosed in 1719, but complaints from seamen led to the removal of the glazing in 1730. Sailors remembered the good blaze from the open fires as being more conspicuous than the steady, but lesser blaze from the enclosed fires.

The material used as a fuel to produce the light is an illuminant. Examples of illuminants are candles, coal, torches and pitch fires, wood, oil, kerosene (paraffin), gas, electricity.

As in Antiquity, a lighthouse consisted usually of a stone tower burning wood, coal or torches in a grate on its summit in the open air, or of a tower or pole on which a keeper hoisted an iron basket containing burning coal or pitch. Sometimes moveable or built-in lanterns with windows of horn or thick glass protected oil lamps or candles. The cost of maintaining these lighthouses was often considerable: stocks of fuel had to be obtained and transported, and attendants had to be paid for the arduous task of keeping fires bright by stacking, stirring and blowing during the night and for frequent trimming of the wicks of oil lamps and snuffing of candles. The oil lamps, smoky and difficult to regulate, unless one were content to show only a tiny flame of which the total light value was small, bore little resemblance to the lamps introduced in 1782. The candles also differed greatly from their modern types. In northern Europe, where the nights of summer were short, the fires were not kindled for several months of the year. [Stevenson, 1959, p17]

1100 After the passing of the Dark Ages, sea-lights were established anew in Europe, commencing about 1100 A.D. at the entrances to Italian ports. Their illumination was given by oil lamps or candles sheltered in lanterns but in northern Europe coal fires burning in the open were preferred. Contemporary accounts of the tall Lanterna of Genoa, lighted in encouraged the establishment of more lighthouses throughout Europe. Before 1586 the navigable channels of Dutch and German rivers were marked by beacons and buoys which by shape and colour directed ships to port or starboard. [Stevenson, 1959, p17]

1500 After 1500, coal became increasingly used in Europe and was found to be better than wood in being more compact, burning longer and requiring less attention from the keepers. Coal was used far more extensively in north-west Europe where it was more readily available. In the Mediterranean, candles and oil lamps were favoured, coal being too expensive. For example, Tynemouth, the earliest British lighthouse of value to shipping was situated adjacent to a coal field. It was natural to use coal when the lighthouse was established in 1550. Similarly, coal fields were close to the Isle of May lighthouse in Scotland when it was set up in 1636.

1581 Reference is made to the burning of coal on a turret at the east end of the priory church at Tynemouth in 1581, although it is almost certain that this was done well before that year. It was rebuilt in 1664 at the north-east corner of the castle. [Hague, 1975, p17]

1581 It is known that the earliest of a succession of lights displayed at Tynemouth was of coal burnt upon a turret at the east end of the priory church. In 1581 it was referred to as having been established 'in former times'. It was rebuilt in 1664 at the north-east corner of the castle. [Hague, 1975]

1600 In Britain, the use of coal fires in major navigation lights was 1 out of 1 existing in 1600, 12 out of 15 existing in 1700, and 21 out of 26 existing in 1760. This excluded the Eddystone and two lightships which could not have had coal fires and were lit by candles or oil. Of the 21 lighthouses in 1760, ten of these had additional lights, of which five were coal and five were oil or candle lights. At the Casquets, there were three coal fires, the only lighthouse of its kind to use three lights. St Bees was the last lighthouse in Britain to use coal, being converted in 1823.

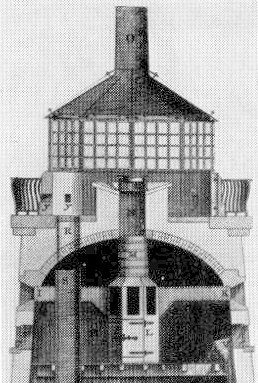

Artist's impression of the 16th c. lighthouse at Tynemouth

1600 Only one major navigational light exists at this time in Britain, a coal fire adjacent to the coal fields of Tynemouth. Stevenson, 1959, p2731600 Only one major navigational light exists at this time in Britain, a coal fire adjacent to the coal fields of Tynemouth. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1636 This was the first Scottish lighthouse is built on the Isle of May. The Scots Council grant a patent for the building of a lighthouse on the Isle to James Maxwell and John and Alexander Cunningham for 19 years at a rental of one thousand pounds "in coin of this realm" equalling £84 sterling. The tower was built the same year. This was to be a famous coal-burning lighthouse for 180 years during the period from 1636 to 1818. The original structure still stands. [Stevenson, 1959, p37; Munro, pp25-38 124]

1700 Fifteen major navigational lights exist in Britain, of which 12 are coal fires. Of the five main lighthouses on the French Atlantic coast, one burned wood and one burned oil. In Sweden, four out of the five existing lights burned coal. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1727 Metal plates for use as mirrors were used by Bitry with a coal fire at Cordouan in 1727, but, although they may have improved the light intensity slightly, the problem with soot deposition probably rendered them totally ineffective after a short time.

1727 The first idea of economising light, by the means of reflectors, is met with in the history of the Cordouan light. M. Bitri, who remodelled the lantern in 1727, arranged it for burning pit coal, of which 225 lbs. (French) were ignited at once, and lasted the night. Above the fire, instead of having a hollow cupola, as it had previously been, or of being entirely open like other Lighthouses, the circle of the ceiling of the cupola was made the base of an inverted cone, whose apex projected downwards three feet; the whole surface of this was covered with tin plates. These becoming reflecting surfaces, served to increase the intensity of the light; but how they were kept free from tarnish, and the effects of the smoke, we are not informed. Here we have the first element of the reflector system, and it is virtually the principle of the present Bordier-Marcet apparatus. Such an arrangement would certainly answer its requirements as applied to a coal fire, and any improvement on it must be also made in conjunction with some better mode of producing a light. [Findlay, 1862, Ch. III]

1753 The traders in Turku in Finland, then Swedish territory, introduced a novelty in lighting when in 1753 they established a lighthouse at Uto at the north entrance to the Gulf of Finland. This islet lies on the southern edge of the extensive archipelago of the Aland islands. The tower, 24 feet high and shaped like a cone, was constructed of quarried stones and boulders and bore a glazed lantern. A pole projecting from the side of the tower carried an iron bucket which, every night, burned coals continuously in the open air. This formed the main fire and it was visible round the sea horizon. The lantern contained a subsidiary light consisting of a cluster of candles and a screen or reflector which was turned abruptly by hand every 15 minutes to light first one and then the other of two navigable channels 15 feet apart. Thus, alternately, ships in one channel saw this subsidiary light while those in the other channel could not see it. A few years after erection of the tower, the light in the lantern was described as coming from 6 lamps each with 2 wicks, hanging from the ceiling, with 4 tinned mirrors behind. The benefit of the arrangement to occult the light lay in economy of oil and not in distinction from other lighthouses. Though the screen or reflector cost 8oo out of the total capital expenditure of 19,280 silver thalers, the apparatus is stated to have been extremely primitive and unpractical. But interest arises from its being an early instance of occulting a sea-light. [Stevenson, 1959, p48]

1760 21 out of the 25 major navigational lights in Britain use coal, excluding Eddystone and two lightships which, by their nature, must use candles or oil lights. Of the six French lighthouse, four burned coal and one wood or coal. In Sweden, four out of six lighthouses burn coal. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1774 Before choosing an illuminant for the new lighthouses in Normandy, the Rouen Chamber of Commerce carried out comparative tests of an open coal fire, a spherical metal reflector from Sangrain and a parabolic reflector from Hutchinson, and made trials of French, Spanish and British coals. An open fire from British coal appeared to be best suited to the requirements and probably was the right choice from the three alternatives but it led to 5 years of trouble for the Chamber. [Stevenson, 1959, p52]

1774 A test is carried out to compare a coal fire with an oil light fitted with a parabolic reflector by Hutchinson. The coal fire was preferred because at that time the oil lamp was too focussed and could not illuminate a big enough part of the horizon. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1776 For 80 years the coal swape lights at the Spurn satisfied seamen making the entrance to the Humber, but by 1766 the sands in the estuary had shifted so much that the navigable channel was far distant from the lights. John Angell, a relative of the first patentee, declined to move them and shut himself in his house and refused to discuss the problem. But his partner Leonard Thompson, who had a quarter-share in the ownership, agreed to Trinity House promoting an Act of Parliament to authorise the building of lighthouses in better positions. When the Act was obtained, Trinity House instructed John Smeaton to visit Spurn Point. On his recommendation, two temporary lights, 250 yards apart, were erected in 1767, both swapes as before, with the coal buckets hoisted 50' and 35' above ground level. A paved path 3' wide with a handrail at each side guided the keepers when passing between them at night. To provide for a possible further shifting of the sands, the larger temporary swape was set on rollers so that it could be moved according as the navigable channel shifted. On 5th September 1776 his two brick towers 90' and 50' high which had been capped by 'inclosed lanterns for fire lights' were lighted. The novel design of their grates, good ventilation of the lanterns and excellent means for raising coals and removing cinders would justify a claim that they were the first scientific coal-burning lighthouses. The chief improvement, as described in Section XVI, consisted of a shallow grate with a controlled supply of air which kept the layer of coals at a whiter or more luminous heat than had been achieved previously with coal fires, but it is likely that the small-capacity grate required too continuous an attendance by the lightkeepers. Not until July 1819 were these two coal fires replaced by oil lamps and parabolic reflectors. Smeaton recorded that his new lighthouses on their first exhibition gave 'an amazing light to the entire satisfaction of all beholders' and that 'vessels going round the Point in a dark night have the shades of their masts and ropes cast upon their decks'. [Stevenson, 1959, p53]

An image of the old lantern at Spurn Point

1776 Smeaton used a funnel to provide a draught with the coal fire in an enclosed lantern at Spurn Point in 1776.

1780 In full blaze, a good coal fire was better for navigation than any other form of unmagnified lighting. Coal fires declined in use after 1780 when the use of parabolic reflectors with oil lamps was understood and used to produce even better lights.

1782 Obtaining coal and transporting it by sea to the rocky shelves of Cordouan had always been troublesome and by 1780 had become extremely expensive. The Government Departments in Paris welcomed the economy achieved from replacing coal fires by spherical reflectors and oil lamps at the lighthouse of St. Mathieu and at those in Normandy, and invited Tortille Sangrain to visit Cordouan and state his price for replacing its coal fire by a reflector light. His tender was accepted and, accordingly, Bitry's open lantern of 1727 was removed and a new metal lantern, completely glazed, to hold no fewer than So tiny silvered spherical reflectors each with an oil lamp was set on top of the tower. The light was exhibited in November 1782 and was condemned at once by seamen who complained of its poor visibility. The keepers also had difficulty in attending to the multitude of smoky lamps. As described in Section XII Joseph Teulere one of the engineers at the fortress of Bordeaux who had charge of Cordouan, was directed from Paris to examine the new light; he pointed out its defects to Sangrain who fitted larger spherical reflectors, but the seamen remained dissatisfied and demanded a return to the coal fire. Their objections were well-founded: the spherical reflectors did little more than obstruct the light from the lamps but were nevertheless retained until 1790 when a better light could be procured. [Stevenson, 1959, p61]

1787 A similar type of light to that of Groves was designed and built by Smeaton to replace one already in use at Spurn Point in 1787. True to form, Smeaton added his own novel design features such as a small umbrella to protect the rope from falling cinders. He found that with a well balanced beam the operation of filling the bucket with a shovelful of coals ad hoisting it could be carried out in a few minutes and eased the keepers work.

1788 Commencing in 1788, Anders Polheimer, who had interests in coal-mining, investigated the operation of the coal-burning Swedish lighthouses of Nidingen, Kullen, Falsterbo and Gronskar, and then devised a new form of grate which he fitted first at Kullen in the summer of 1792. He left it open to the air, as was usual in Sweden, but he provided that the light-keeper could regulate the fire in the grate by means of a door set in the space between the walls. When this was opened a strong draught passing upwards through a pipe induced a brighter and more uniform blaze from the coals. Before and after installing the new grate the keepers at Kullen recorded nightly the quantity of coals burned, the weather conditions and the direction and force of the wind. The records revealed that the economy resulting from the alteration was merely proportional to the reduction in the size of the grate, but seamen enjoyed a better beacon fire. [Stevenson, 1959, p70]

1790 Mirrors were of little value with coal fires, although they were known to be used at Harwich high lighthouse, where, between 1790 and 1809 metal plates were set behind the open coal fire.

1800 Assuming that a ton of coal was equivalent to 45 cubic feet, in December 1800 the keepers had to place 4 cwts of coal in the grate every hour. The grate had a diameter of 3 ft 6 ins (1.1 m) and a depth of 2 ft (0.6 m). It was raised on legs on the top of the tower and burned without roof or screen every night of the year. It is easy to imagine how hard the work was for the keepers. Large quantities of heavy coal had to transported about, loaded on and off boats, transported along rough cart tracks and across bogs. Finally came the work in raising the coal to the height necessary to burn it.

1800 Funnels were used to provide draughts for coal fires at Danish, Swedish and Norwegian lighthouses after 1800. All these lighthouses had enclosed lanterns.

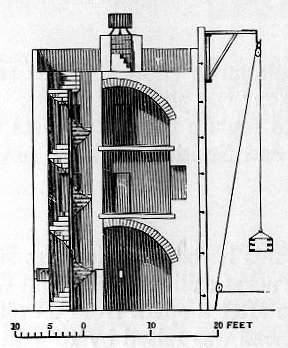

A section through the coal-burning tower at the Isle of May

1814 Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson visited the Isle of May light and were told that the light from the coal fire was visible in a strong wind only from one side of the island. [Stevenson, 1959, p281]

1820 Gas obtained from coal was considered possible for use as a fuel for light sources in lighthouses around 1820. However, plans to manufacture the coal gas at the site of the lighthouse were not executed. coal still had to be transported and it was necessary to install plant to make the gas and to give the keepers skills in its operation. It was felt that there was no advantage to be gained in doing this in this way at this time.

1820 Gas obtained from coal was considered possible for use as a fuel for light sources in lighthouses. However, plans to manufacture the coal gas at the site of the lighthouse were not executed. coal still had to be transported and it was necessary to install plant to make the gas and to give the keepers skills in its operation. It was felt that there was no advantage to be gained in doing this in this way at this time. [Stevenson, 1959, p278]

1823 The use of coal fires has not been so long abolished as might be imagined. In Britain they were used till 1823. Thus the Isle of May Lighthouse, at the entrance of the Firth of Forth, had a coal fire till 1810; at St. Bees Head, Cumberland, oil was first used in 1823; at the Flatholm, Bristol Channel, in 1820, &c. [Findlay, 1862, Ch. III]

1823 The last lighthouse in Britain to use coal, St. Bees, is converted to oil. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1846 It is stated that a coal fire is still used on the Gronskar Lighthouse, East coast of Sweden. They were in operation on the two towers of Nidingen, in the Cattegat, till 1846. [Findlay, 1862, Ch. III]

1854 All coal burning lighthouses in Sweden were discontinued. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1858 The last coal fire lighthouse in Europe, at Villa in Norway, is discontinued. Stevenson, 1959, p2731820 Gas obtained from coal was considered possible for use as a fuel for light sources in lighthouses around 1820. However, plans to manufacture the coal gas at the site of the lighthouse were not executed. coal still had to be transported and it was necessary to install plant to make the gas and to give the keepers skills in its operation. It was felt that there was no advantage to be gained in doing this in this way at this time.

1820 Gas obtained from coal was considered possible for use as a fuel for light sources in lighthouses. However, plans to manufacture the coal gas at the site of the lighthouse were not executed. coal still had to be transported and it was necessary to install plant to make the gas and to give the keepers skills in its operation. It was felt that there was no advantage to be gained in doing this in this way at this time. [Stevenson, 1959, p278]

1823 The use of coal fires has not been so long abolished as might be imagined. In Britain they were used till 1823. Thus the Isle of May Lighthouse, at the entrance of the Firth of Forth, had a coal fire till 1810; at St. Bees Head, Cumberland, oil was first used in 1823; at the Flatholm, Bristol Channel, in 1820, &c. [Findlay, 1862, Ch. III]

1823 The last lighthouse in Britain to use coal, St. Bees, is converted to oil. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1846 It is stated that a coal fire is still used on the Gronskar Lighthouse, East coast of Sweden. They were in operation on the two towers of Nidingen, in the Cattegat, till 1846. [Findlay, 1862, Ch. III]

1854 All coal burning lighthouses in Sweden were discontinued. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]

1858 The last coal fire lighthouse in Europe, at Villa in Norway, is discontinued. [Stevenson, 1959, p273]